The West Harris County Regional Water Authority (WHCRWA or West Authority) was created by the Texas Legislature to identify and secure a long-term supply of quality drinking water at the lowest responsible cost, to promote water conservation, and to facilitate compliance with groundwater reduction strategies and mandates. In 2003, the WHCRWA successfully negotiated a long-term water supply contract with the City of Houston, and design and construction of the necessary transmission lines and facilities began. In 2010, WHCRWA met the first of the Subsidence District’s groundwater reduction mandates by converting to more than 30 percent surface (or alternate) water. The next mandate is to increase surface water usage to 60 percent by 2025.

The West Authority is not a MUD and does not control any MUD operations (delivering water to homes and businesses, sewer services, billing, etc.). The West Authority is a wholesale provider and does not provide retail water services. If you have a question about your retail water or sewer services, please contact your MUD customer service number for information and assistance.

To find out more about what a MUD is and does, go here https://www.tceq.texas.gov/waterdistricts

The West Authority was created by the Texas Legislature in 2001 to facilitate the shift from pumping underground well water to surface water supply (water from lakes and rivers) by municipal utility districts (MUDs) in west Harris County, and the City of Katy. When large sections of Harris County – primarily to the north and west of the City of Houston – were directed by the Harris-Galveston Subsidence District to convert to 80 percent surface water supply over the next 20 years, there was no centralized government that could take on the task of negotiating and securing a long term supply of water from the City of Houston or other entities that had surface water to sell. Harris County did not have the right to own, operate and sell water, so it was up to the municipal utility districts to figure out how they would do it on their own. It was a monumental task for the individual MUDs, so four large water authorities – the West Harris County Regional Water Authority, North Harris County Regional Water Authority, Central Harris County Regional Water Authority, and the North Fort Bend Water Authority in Fort Bend County — were created to manage the supply challenge and to design and construct new water delivery systems for their respective areas.

The West Authority is made up of municipal utility districts (MUDs) and the City of Katy. It is governed by a Board of Directors that includes nine directors who represent Voting Precincts made up of the individual MUDs, and the City of Katy, and serve staggered four-year terms.

The primary mission of the WHCRWA and its governing board is to:

- Acquire and provide surface water and groundwater for residential, commercial, industrial, agricultural, and other uses;

- Reduce groundwater withdrawals;

- Promote the conservation, preservation, protection, recharge, and prevention of waste of groundwater, and of groundwater reservoirs or their subdivisions; and

- Control subsidence caused by withdrawal of water from those groundwater reservoirs or their subdivisions.

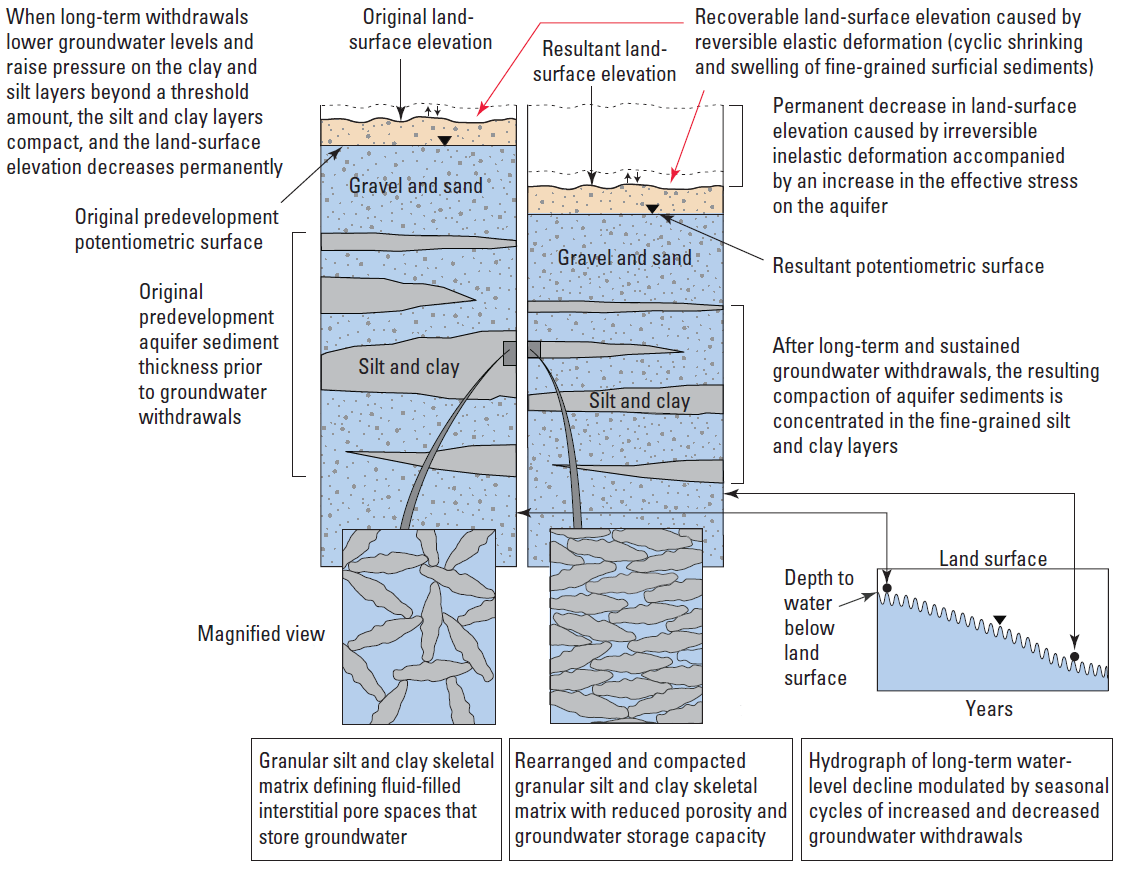

Until the 21st Century, most residents who lived in Harris County, but outside of the City of Houston city limits, got their water from wells tapping into underground aquifers. This water has been delivered to homes and businesses by hundreds of individual MUDs and when the faucets were turned on…water came out. People were blissfully unaware that the aquifers that had provided what seemed like an endless supply of drinking water were beginning to decline. We are moving to surface water because the underground water supply we have traditionally relied on is shrinking.

In addition, as the county has grown, the underground water has become so depleted in some areas that the ground above it has begun to sink, a process known as subsidence.

The Harris-Galveston Subsidence District (Subsidence District or HGSD) was created by the Texas Legislature in 1975 as the first entity of its kind in the U.S. with the power to restrict groundwater withdrawals and prevent subsidence. Initially, the Subsidence District addressed the severe subsidence occurring in the Baytown-Pasadena-Galveston area — where whole subdivisions had to be abandoned after sinking below sea level — by requiring industries on the Houston Ship Channel to convert to surface water. The results were dramatic — subsidence in the Baytown-Pasadena area was significantly improved, and has since been largely halted altogether. Next, the municipal utility districts (MUDs), cities and private well owners in north and west parts of Harris County were told that they must use 80 percent surface water by 2035.

As it grew increasingly clear in the latter part of the 20th Century that the Houston-Galveston region needed to reduce its dependence on groundwater, the City of Houston started deactivating its water wells and building water treatment plants that could purify surface water from lakes and rivers.

The Harris-Galveston Subsidence District — a special purpose district created by the Texas Legislature in 1975, the first of its kind in the U.S. – was authorized to “end subsidence” and was armed with the power to restrict groundwater withdrawals. After the City of Houston converted areas along the Houston Ship Channel to surface water supplied from the recently completed Lake Livingston reservoir, subsidence in the Baytown-Pasadena area was dramatically improved and has since been largely halted. But as subsidence was stabilizing in the coastal areas, groundwater levels in inland areas north and west of the City of Houston were rapidly declining.

The Harris-Galveston Subsidence District’s goal was to achieve the same improvements in west and north Harris County so water providers were told to seriously cut back on pumping groundwater from wells and to replace it with surface water. The Subsidence District set deadlines: 1) Convert to 30 percent non-groundwater water use by 2010; 2) Convert to 60 percent non-groundwater water use by 2025; and, 3) Convert to 80 percent non-groundwater use by 2035. Failure to reach these goals would trigger payment of steep penalties.

Residents in west Harris County have traditionally relied on groundwater pumped from individual wells by municipal utility districts or other water suppliers. Not many people realized that there was a growing problem with land subsidence in their area, or that aquifers supplying the region were beginning to decline. Few noticed when — in the early 1970’s — just 50 miles south an entire subdivision was overwhelmed by flooding and sank into the marsh.

The Harris-Galveston Subsidence District — created by the Texas Legislature to “end subsidence” — was armed with the power to restrict groundwater withdrawals. The District issued its first groundwater regulatory plan in 1976, prompting industries on the Houston Ship Channel to convert to surface water supplied from the recently completed Lake Livingston reservoir. As a result, subsidence in the Baytown-Pasadena area was dramatically improved, and has since been largely halted.

Illustration of subsidence in a Gulf Coast aquifer as a result of groundwater withdrawals producing a decrease in the potentiometric surface (the groundwater level). Source: Kasmarek, M.C., Ramage, J.K., and Johnson, M.R., 2016, Water-level altitudes 2016 and water-level changes in the Chicot, Evangeline, and Jasper aquifers and compaction 1973–2015 in the Chicot and Evangeline aquifers, Houston-Galveston region, Texas: U.S. Geological Survey Scientific Investigations Map 3365, pamphlet, 16 sheets, scale 1:100,000, http://dx.doi.org/10.3133/sim3365.

Subsidence comparison of Brownwood Subdivision

Use the divider in the middle of the photos to the right to compare Brownwood from 1944 to 2002

The West Harris County Regional Water Authority represents an area located between U.S.290 and the Harris-Waller county line that is larger than the City of Pittsburgh.

The North Harris County Regional Water Authority is responsible for an area located generally between U.S.290 and U.S. 59; and the Central Harris County Regional Water Authority is made up of 11 MUDs in the area near SH 249 and Beltway 8. The North Fort Bend Water Authority includes the City of Fulshear and MUDs in Fort Bend County located south of I-10, east of the western area of Fulshear, north of the cities of Sugar Land, Richmond and Rosenberg, and west of the Fort Bend-Harris county line.

Water Supply Overview

A Groundwater Reduction Plan (GRP) outlines and explains how a water provider will reduce well water usage to only 20 percent by 2035, and it must be approved by the Subsidence District. The West Authority has an approved plan for its service area and is implementing the surface water conversion plan outlined in its GRP.

The West Authority was charged with finding a reliable source of surface water (water from rivers, lakes, etc.) that could be delivered to MUDs in west Harris County so that they could reduce reliance on pumping underground water.

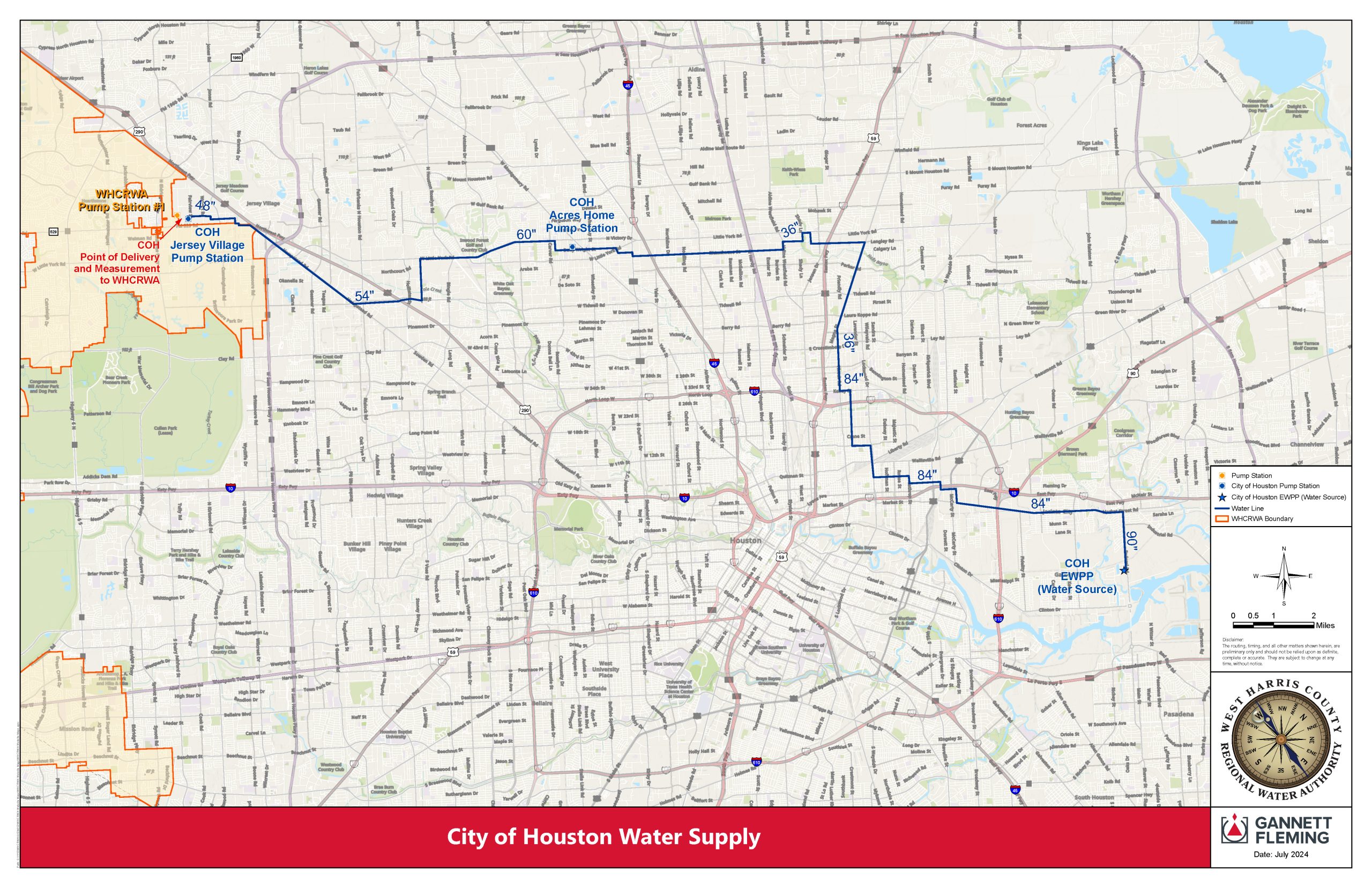

Though there were several public and private entities that own water rights in our region, the City of Houston has been securing water rights and property for reservoirs since the early 20th Century and now has three reservoirs available for its water supply – Lake Houston and Lake Conroe on the San Jacinto River and Lake Livingston on the Trinity River. In addition, the City of Houston has three water treatment plants that can purify several hundred million gallons of water a day. The City of Houston had water to sell and it was geographically desirable.

In 2003, the West Authority reached an agreement with the City of Houston to partner in a water supply contract; the West Authority purchased the right to a certain amount of capacity in the city’s East Water Purification Plant and the right to purchase future capacity in the City of Houston’s Northeast Water Purification Plant, as well as space in some of the transmission pipelines that transport water from the plants to west Harris County.

The surface water used in the West Authority comes from the City of Houston, which owns the majority of surface water in the Houston region. The City of Houston owns three reservoirs – Lake Houston in north Harris County, Lake Conroe in Montgomery County and Lake Livingston in Trinity County. Currently, the City of Houston treats water from Lake Houston and Lake Livingston and moves it through large transmission lines to water customers throughout the region, including the West Authority.

There are several potential consequences of not moving to surface water, including additional land subsidence, which could lead to the failure of groundwater wells and increased risk of flooding in the areas that subside.

Prior to the 1970s, the majority of the Houston-Galveston region’s water supply came from wells that pumped water from underground sources, and that was taking its toll on the land that homes and businesses were built on. As the water underneath was drawn down, the ground above began to compact and sink – or subside – into the empty space where water was once stored naturally.

The most startling example of subsidence in the Houston region was the sinking of the Brownwood neighborhood near the Houston Ship Channel. Between 1943 and 1973, about 4,700 square miles of land southeast of downtown Houston sank at least six inches, with the area near the Ship Channel and Brownwood sinking about nine feet. Because it happened slowly, many did not realize its full effect until people’s homes began flooding regularly. Some structures were swallowed by the bay, and those that survived eventually were declared uninhabitable after Hurricane Alicia completed the devastation in 1983.

In 1975, the Texas Legislature created the Harris Galveston Subsidence District to regulate groundwater usage in Harris and Galveston counties to prevent additional land subsidence. After the District’s success in arresting subsidence southeast of Houston by regulating groundwater pumping, Harris County water providers were also required to seriously cut back on pumping groundwater from wells and to replace it with surface water, such as that from lakes and rivers. Failure to comply with the Subsidence District mandates triggers payment of “disincentive fees,” which are increasingly steep penalties.

The Harris-Galveston Subsidence District is allowed to charge a “disincentive permit fee” to water providers that do not meet surface water conversion deadlines, which are: 1) Convert to 30 percent non-groundwater use by 2010; 2) Convert to 60 percent non-groundwater use by 2025; and, 3) Convert to 80 percent non-groundwater use by 2035.

The current disincentive fee (as of Jan. 1, 2025) is $12.12 per 1,000 gallons of well water pumped. In other words, if a MUD or water authority does not meet the conversion requirements each year, it is charged $11.86 per 1,000 gallons of well water pumped over the amount allowed until it meets the requirement. This could end up being an extremely expensive proposition.

No, the West Authority has no taxing authority, but does charge a fee for water pumped by, and surface water delivered to, the utility districts and well owners in its boundaries in order to pay its costs.

Pumpage and Surface Water Rates effective 1/1/2024

Groundwater – $3.95/1,000 gallons and

Surface Water – $4.35/1,000 gallons

The West Authority fee that appears on residents’ water bill is charged for water pumped by the utility districts (well pumpage fee) and for surface water (surface water fee) provided to them by the West Authority. The utility districts in turn charge their individual customers for the water they use, and are permitted to modify the fee charged them by the West Authority to cover such things as leaks in their system, fire hydrant use, etc.

These fees generate funds needed to design and construct the infrastructure necessary to deliver surface water to the neighborhoods in order to comply with the Subsidence District’s phased mandates.

It is more expensive to treat and deliver surface water than it is to produce and deliver underground water. Groundwater wells are generally located in the area they “serve” and distribution lines to homes and businesses were constructed when the subdivisions or neighborhoods were built. The conversion to surface water requires that a whole new infrastructure be designed and constructed, including transmission and distribution lines – a process that involves the costly negotiation for and/or purchase of rights of way.

The short answer is, “Yes.” WHCRWA must charge sufficient rates to cover debt service payments and operating costs. Looking at the projected bond requirements over the next few years, a large amount of money is going to be needed as the transmission and distribution projects move from the design phase into the construction phase.

Since its creation the Board has set fair and reasonable rates, and has relied on the services of an independent rate analyst to: consider the costs related to carrying out the mission of the West Authority; the funding needed to comply with the HGSD conversion mandates; and to pay our share of the massive infrastructure projects – our share of which is OVER $1.5 Billion.

WHCRWA has its own Capital Improvement Projects – the distribution lines, storage facilities and pump stations to deliver water to the community. We will continue to update the Rate Study as information becomes available about construction costs and to do everything possible to hold prices down.

The West Authority anticipates being finished with the surface water conversion process for the MUDs and water providers within its boundaries by 2035, which is the deadline set by the Harris-Galveston Subsidence District.

The cost of water will continue to rise. The West Authority Board of Directors is committed to keeping the cost of water as low as possible for as long as possible and will keep the periodic rate increases reasonable and consistent with this commitment. Increasing the West Authority fee steadily and in smaller amounts will help avoid a sharp increase in the fee in the years ahead.

Projecting rates is difficult due to unpredictable financing and construction costs. Annual rate increases must be approved by the Board. Click here to view the WHCRWA pumpage fee history

All public and private water providers, including municipal utility districts (MUDs), in north and west Harris County are required to meet the Harris-Galveston Subsidence District’s requirement to convert to using 60 percent non-groundwater by 2025 and 80 percent non-groundwater by 2035. They have to meet this requirement whether or not they are part of a larger group, such as the West Harris County Regional Water Authority. If a water provider – or a water authority – does not meet the HGSD’s deadlines, they face paying a fine of $10.78 for every 1,000 gallons of well water pumped from the ground over the amount allowed by the HGSD. Those fines could add up quickly.

Being part of the West Authority’s Groundwater Reduction Plan (GRP), and paying related fees, provide MUDs with compliance of HGSD rules so that MUDs can avoid HGSD’s disincentive fees.

The West Authority uses the fees collected to fund its capital, operations/maintenance and debt service budgets. The vast majority of budgetary allocations go toward buying surface water, and planning and building the system needed to deliver surface water from City of Houston-owned reservoirs to the MUDs in the West Authority boundaries.

A large amount of money is needed to accomplish these goals. The WHCRWA has to charge sufficient rates to make debt service payments on loans secured to build the projects and to cover operating costs for the infrastructure we already have in the ground.

The current estimated additional cost of the West Authority’s surface water conversion effort is more than $1.5 billion.

SWIRFT — established by the Texas Legislature and approved by voters in 2013 to fund projects in the State Water Plan — was created through the transfer of a one-time, $2 billion appropriation from the State’s “Rainy Day Fund.” This money will be leveraged with revenue bonds over the next 50 years to finance approximately $27 billion in water supply projects throughout Texas.

The State Water Implementation Revenue Fund for Texas (SWIRFT) is authorized to offer multi-year, low interest loans for water projects.

For more information about SWIRFT and other Texas Water Development Board programs, go to www.twdb.texas.gov.

The Texas Water Development Board (TWDB) approved three financial assistance applications for SWIRFT submitted by the West Authority in 2015. The multi-year, low-interest loan commitment was for a total of $812,140,000. With SWIRFT funding, the West Authority expects to save more than $400 million in debt service payments on low-interest bonds to fund the construction of a regional network of pipelines, pump stations and water treatment and storage infrastructure that will one day bring up to 150 million gallons of treated surface water a day to residents in northwest and west Harris County, and northern Fort Bend County.

The Texas Water Development Board (TWDB) approved an additional $50 million commitment to the West Authority in 2017 through the State Water Implementation Revenue Fund for Texas (SWIRFT) administered by the TWBD. The original multi-year commitment approved for West Authority projects in 2015 was approximately $812 million, and in late July 2017, the TWBD made an additional $50 million available, which the West Authority will use to partially fund its share of costs needed to expand Houston’s Northeast Water Purification Plant by 320 million gallons per day. Partners in the project include the City of Houston, the West Authority, the Central Harris County Regional Water Authority, the North Fort Bend Water Authority, and the North Harris County Regional Water Authority.

The lower interest rates attached to SWIRFT bonds, as opposed to interest rates available in the general bond market, result in significant cost savings for the West Authority and its residents over the life of the loans. Municipalities, counties, water authorities and other water providers whose projects have been included in regional water plans can apply for SWIRFT funding. The state adopted this new approach to funding to help these entities turn water plans into water supplies.

Yes. In 2018 the Texas Water Development Board approved two new commitments: $50 million for additional funding for the expansion of the Northeast Water Purification Plant, and an additional $45 million for the Surface Water Supply Project.

The WHCRWA’s source of alternative water will be the City of Houston (COH) pursuant to a water supply contract entered into in 2003 and supplemented in 2009 and 2015.

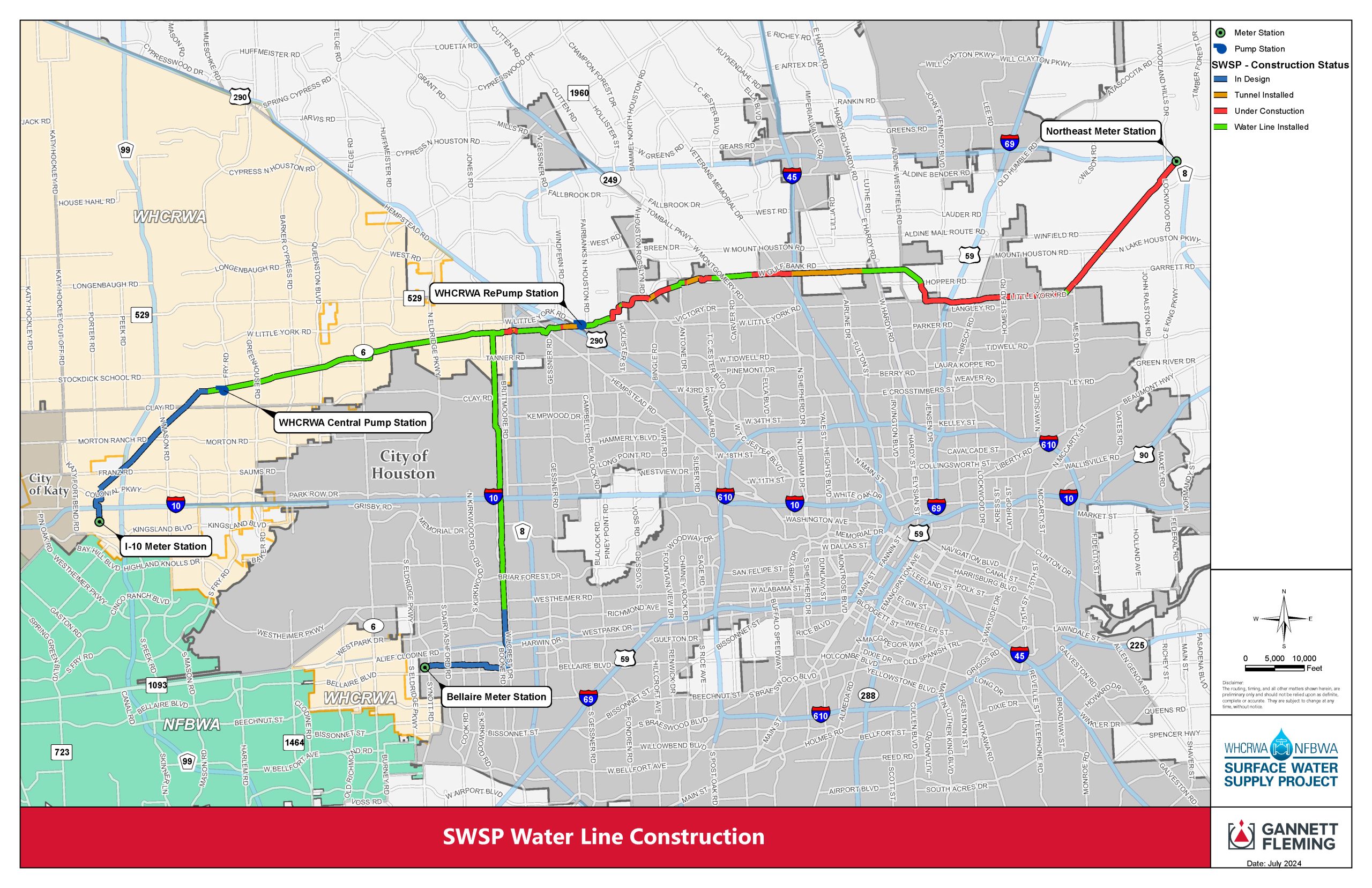

Since 2010, the supply point for COH surface water to the WHCRWA is the COH’s Jersey Village Pump Station located on Fairview Street north of FM 529, west of COH city limits. The water is supplied from the COH’s East Water Purification Plant (EWPP) and conveyed through existing transmission mains. For 2025 and beyond, the additional source of COH water to the WHCRWA will be from the COH’s Northeast Water Purification Plant (NEWPP) located on Lake Houston. The NEWPP is being expanded to meet the needs of the WHCRWA, other authorities, and the COH for 2025 and 2035 conversion mandates.

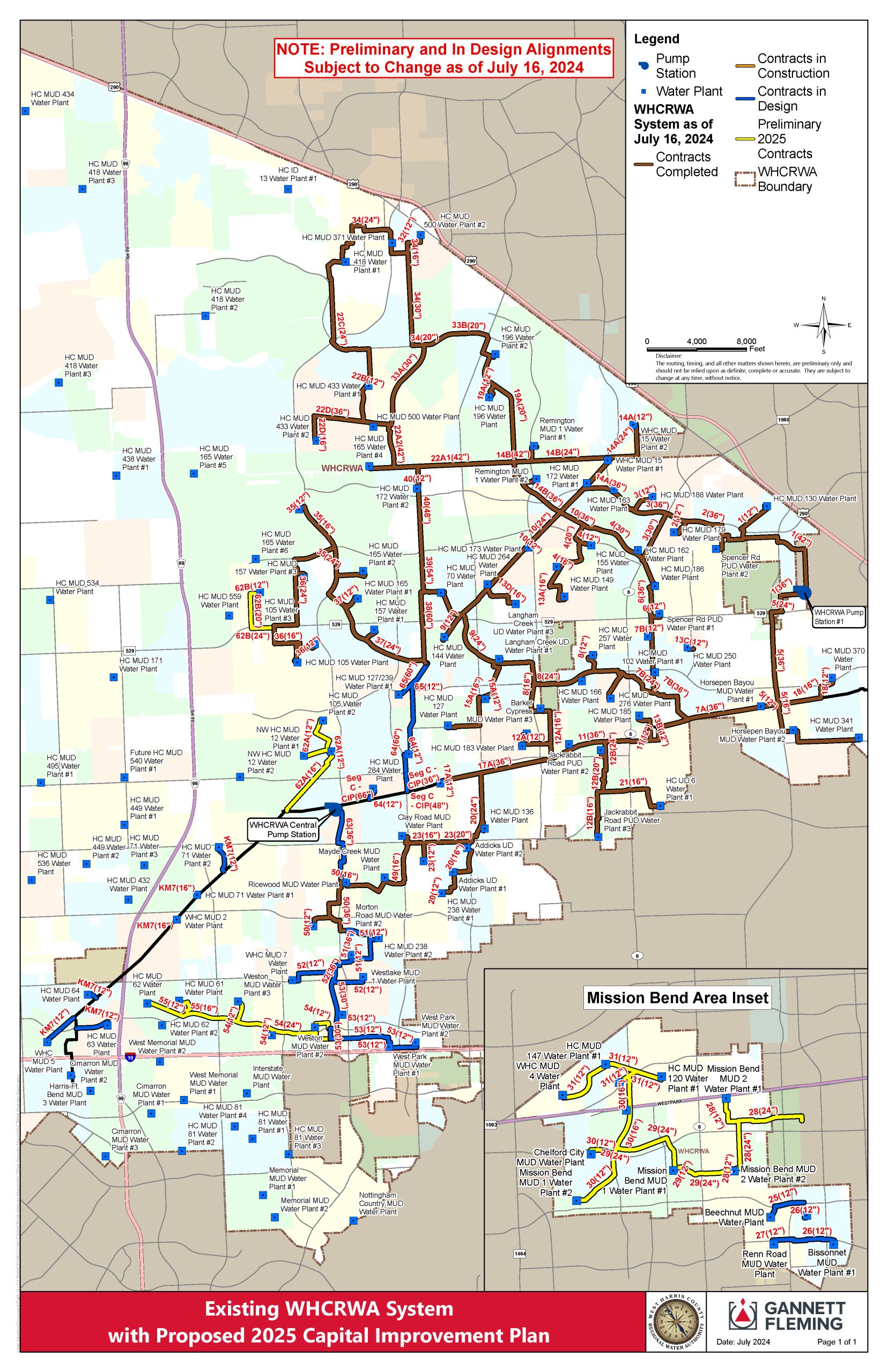

The WHCRWA transmission system was designed to provide adequate water to meet the requirements for conversion to surface water as set forth by the HGSD, which are 30 percent conversion by 2010, 60 percent conversion by 2025, and 80 percent conversion by 2035.

During the construction to meet the 2010 requirements, the WHCRWA built a booster pump station and ground storage tanks in the immediate vicinity to accept the water and boost the system pressure. Transmission lines within the system were designed to provide the average day, peak day, and peak hour flow. Residential fire demands were also considered.

Prior to 2010, the WHCRWA purchased from the COH a total capacity of approximately 28.25 million gallons per day. By 2010, construction of the entire first phase was completed, and the WHCRWA continues to meet the HGSD conversion requirements of 30% alternate water.

The 2010 service area is generally the area bounded by Highway 290 on the north, Brittmoore on the east, Clay Road on the south and Barker-Cypress on the west. The WHCRWA began delivering surface water in 2005.

The Surface Water Supply Project (SWSP) will help to reduce land subsidence and will meet the water needs of a rapidly growing population. In compliance with mandates issued by the Harris-Galveston Subsidence District, and to meet water demands for 2025 and beyond, the WHCRWA is delivering the SWSP. The project also will allow the North Fort Bend Water Authority (NFBWA) to comply with Fort Bend Subsidence District groundwater reduction requirements.

Once complete, surface water from Lake Houston will be supplied to retail water providers (MUDs, PUDs, WCIDs, etc.) in the WHCRWA and NFBWA by way of the City of Houston’s Northeast Water Purification Plant through over 60 miles of pipeline and two large pump stations. These transmission pipelines will vary in diameter from 96 inches to 42 inches, depending on the pipeline segment. Construction of the entire project is expected to take place from 2020 to 2025 and will be completed in segments. In other words, the waterline will be constructed one piece at a time. For additional information, please visit the Surface Water Supply Project website http://www.surfacewatersupplyproject.com.

Water from the City of Houston’s treatment plants run through transmission lines to the West Authority’s pump stations and then to a network of smaller pipelines that deliver surface water to individual MUDs. The smaller pipelines flow to pipes that connect to a MUD’s water plant. From there, the MUD stores the water and sends the water through its own internal pipeline system to homes and businesses.

See the maps page for more details.

MUDs are encouraged to keep their wells operational for contingency, for backup, for peak water demands, and for emergency purposes. If a pipeline that brings surface water to a MUD needs repair, for example, the MUD may need to shift temporarily to well water so that the surface waterline can be shut down while it is under repair. Well water can also be used as a backup water supply if the City of Houston’s water system is temporarily out of service due to weather emergencies or maintenance requirements. Once the 2025 and 2035 mandated reductions are achieved, the MUDs will need their wells to be in good operating condition to provide the balance of water demand – 40% and 20% respectively.

The West Authority completed pipeline projects between 2003 and 2008 to deliver water from the City of Houston’s East Water Purification Plant to municipal utility districts that needed water sooner rather than later as they were experiencing water quality and quantity problems with their wells.

The MUDs connected to pipelines constructed near Highway 6 and West Road in the Copperfield and Horsepen Bayou areas, and near West Little York and Eldridge roads include Horsepen Bayou MUD, Spencer Road Public Utility District and Harris County MUDs 130, 162, 163, 186, 179, 188 and 208. Subdivisions served by those MUDs are Westland, Brookside Court, Copperstone, Wheatstone-Coppercreek, Wheatstone-Copperstone, Wheatstone-Summerfield, Middlegate Village, Northmead Village, Southdown Village, South Creek Village, Easton Commons, Easton Village, Copperfield Place, Gardens at Copperfield, Copper Grove, Point Northwest, Copperfield Southcreek, York Ridge Centre, Concord Crossing, Fairway West, Hearthstone, Concord Bridge, Concord Bridge North, Eldridge Park and McKendree Park.

The pipelines constructed along West Little York Road, between Highway 6 and Barker-Cypress Road, and near the FM 529/Highway 6 intersection include Harris County MUDs 264, 70, 173, 257, 102, 250, 186, Langham Creek MUD and Spencer Road. Those MUDs serve the Concord Crossing, Jamestown Colony, Langham Creek Colony, Georgetown Colony, Cumberland Place, Hearthstone Place, Hearthstone, Fairway West, Copperfield Place, Southdown Village, Sect. 4, 6, 7, Southpoint Village, Copperfield Mall, Ashley Grove, Westcreek Village, Fairfax Landing, Paddock, Westgate, Copper Lakes and Lone Oak subdivisions.

The City of Houston’s water resources will supply the region with water for several decades, but it is prudent to continuously identify additional sources – and water treatment methods — for future generations.

That is what City of Houston leaders did in the early 20th Century when groundwater wells were becoming depleted and causing subsidence. Nearby rivers flowing from places north of the region offered the best alternative. Houston acquired water rights in the San Jacinto and Trinity rivers, and by 1973 had created three reservoirs – Lake Conroe on the San Jacinto River’s West Fork in north Montgomery County, Lake Houston on the San Jacinto River’s East Fork in northeast Harris County, and Lake Livingston on the Trinity River near Huntsville. The water in those reservoirs is sufficient today, but it is important to plan for a time when water supplies in the three lakes could fall short of demand, particularly if the region falls into drought mode.

For example, with regional planners predicting another 2 million residents moving to Harris County by 2040, the City of Houston recognized the need to tap into the additional capacity it owns in the Trinity River.

Luce Bayou Interbasin Transfer Project

The Luce Bayou Interbasin Transfer Project (LBITP) is the largest raw water supply project built in Southeast Texas in the past 50 years. The LBITP transfers surface water to Lake Houston from the Trinity River located in Liberty County, Texas. It is comprised of the 500 MGD Capers Ridge Pump Station, 3 miles of Dual 96-inch Diameter Pipelines, and 23.5 Miles of Earthen Canal. A U.S Army Corp of Engineers Permit (SWG-2009-00188) was approved for the project in 2014 and construction was completed in 2022. The LBITP is currently in operation and supplying water to Lake Houston.

WHCRWA’s share of this project is approximately 70 million dollars and will increase our water demand allocation to 82 million gallons per day and a total water demand allocation of 110 million gallons of water per day.

Northeast Water Purification Expansion Project

The estimated $1.973 billion-dollar Northeast Water Purification Plant (NEWPP) Expansion Project is managed by the City of Houston (COH) and will serve the COH, WHCRWA, NHCRWA, NFBWA, and CHCRWA with each paying their fair share of the cost.

The progressive design build project will add 320 million gallons of treatment capacity to the NEWPP’s existing 80 million gallon per day water treatment plant.

WHCRWA will have a 25.76 percent cost share and 82.42 million gallons per day of treated water.

A Consumer Confidence Report (CCR) is an annual water quality report (or a drinking water quality report) that specifies where your water comes from, what’s in it, and how safe it is. The Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA) requires that every community water supplier – including cities and municipal utility districts (MUDs) – provide an annual report by July 1 of each year to its customers. You may receive this by mail or electronically.

The Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA) is the federal law that protects public drinking water supplies throughout the nation. Under the SDWA, EPA sets standards for drinking water quality and implements various programs to ensure drinking water safety.

Each retail water provider is required to supply customers with the report. Please contact your MUD directly to obtain a copy of the Consumer Confidence Report for its water supply.

In advance of construction, the West Authority contacts homeowner associations, local businesses and other interested parties to answer questions and provide information about waterlines that will be installed near neighborhoods.

The West Authority mails/emails brochures that contain contact information for project managers on each pipeline project. Residents can check the West Authority’s website for updated information and photos of the projects in progress.

Municipal utility districts will also send out a letter to residents prior to their transition to chloramine disinfection, which is an indicator of transition to surface water supplied to residents.

Emails: To sign up to receive informational emails a directly from the WHCRWA, please click here. A link to sign up for emails is also available on the WHCRWA homepage.

Text messages: To sign up for text messages from the WHCRWA, you have two options:

- To sign up for WHCRWA Emergency Alerts text ALERTS to 1-833-385-0216 from your mobile phone or click here to use the form.

The WHCRWA has taken measures to strengthen service during extreme weather events. WHCRWA’s emergency power facilities are maintained throughout severe weather events.

Additionally, the WHCRWA continues to take steps to reduce the risk of losing water supply from the City of Houston:

- Coordinating directly with the City of Houston to assess events leading up to any critical infrastructure failure

- Continuing to survey infrastructure and making repairs to the WHCRWA system where necessary

- Assessing available data regarding the loss of water supply

- Reviewing and revising where necessary, the established emergency plans, including the WHCRWA Operator’s Severe Weather Plan

- Developing long-term mitigation plans to address future extreme weather events

- Enhancing communication methods and measures with utility district customers

- Coordinating with the City of Houston and other Water Authorities in reviewing the Northeast Water Plant Expansion Project for design elements, resilience, and redundancy for operations in emergency conditions.

The WHCRWA Board of Directors has initiated an investigation to consider the option of obtaining groundwater supplies to supplement their surface water delivery plans. There are various options to explore but no decisions have been made at this time.

The WHCRWA has always strongly encouraged MUDs to maintain additional water supply sources in the event of an emergency. WHCRWA urges Well Owners to maintain their wells, and MUDs should also have multiple interconnects, if possible, in the event that surface water is not available. The WHCRWA water supply is not intended to serve as the only water supply source.